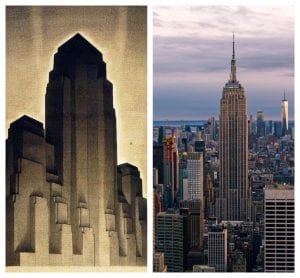

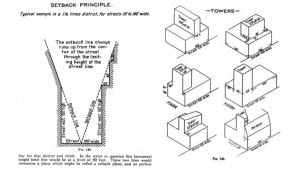

On this day in 1916, New York City passed a zoning resolution which established the maximum mass of buildings allowed on any give site, based on a prescribed vertical height above the street. The multiple setbacks that resulted to maximize floorspace within this restriction created complexity in building envelopes with profound implications for New York’s skyline and SUPERSTRUCTURES’ future work.

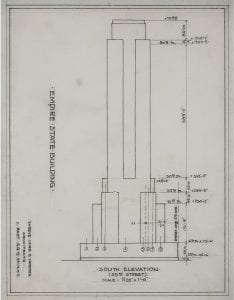

With the 1916 law, any new high-rise had to be stepped back within a diagonal plane projected from the center of the street. Part of the intent, as Manhattan borough president George McAneny put it, was “to arrest the seriously increasing evil of the shutting off of light and air from other buildings and from the public streets, to prevent unwholesome and dangerous congestion both in living conditions and in street and transit traffic.” One of the most important factors in shaping the cityscape, the 1916 regulations held sway until they were revised again in 1961. Towering landmarks such as Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building—the world’s two tallest buildings in 1931—took their shape from the 1916 zoning law.

One of SUPERSTRUCTURES’ first assignments under Local Law 10 (1980) was a critical examination of the Empire State Building’s envelope. Local Law 10 and New York’s Facade Inspection Safety Program (FISP)—embodied in Local Law 11 (1998)—exempted vertical surfaces greater than 25 feet from the street, which typically exempted the second setback, if not the first. Even though the Empire State Building is 102 stories tall, thanks to the setback exemption we only needed to examine the first 30 stories or so, mitigating an otherwise herculean rigging and inspection task.

14 Wall Street, 25th Floor, New York, NY 10005

(212) 505 1133

info@superstructures.com

Subscribe to SuperScript, our email newsletter.