“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually, then suddenly.” - Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

The building envelope behaves the same way.

Gradually, minor masonry cracks widen, leaks worsen, and sealant failures are neglected until suddenly, a section of parapet crashes to the street, a sidewalk vault collapses, or a roof leak ruins a priceless set of first-edition Hemingway novels.

Hemingway’s clever point is that Mike’s bankruptcy might have been “sudden,” but it should not have been unexpected.

That’s why SUPERSTRUCTURES advocates regular, proactive maintenance, even for facades that are not subject to New York City’s Facade Inspection Safety Program (FISP). Many of our clients’ buildings are institutional facilities (some of the most prominent buildings in NYC) that are shorter than seven stories.

While degradation of individual building components such as corrosion of steel beams, mortar joint erosion, or roof membrane weathering tends to be constant over time, failure of building systems (interrelated building elements) increases more dramatically with age. That increase translates into exponentially rising repair complexity—and costs.

Consider, for example, the parapet wall of a typical pre-war office or apartment building. Its system typically includes: coping stones, the mortar or sealant between them, the masonry parapet itself, the concrete roof slab, and the steel beams that support it all. When all the elements of this system are new or in good repair, the coping stones and their mortar or sealant protect the underlying components from the elements.

But time marches on. Small cracks in the coping stones and breaches in their mortar and sealant develop, allowing water to infiltrate the masonry below. The water freezes and expands, acting like a wedge which can force the parapet masonry outward. Breaches continue to grow, allowing more water to intrude. Water migrates down through the concrete roof slab (not inherently waterproof) to the steel framing. The steel beams begin to rust, expanding and pushing the parapet even further outward. Rinse, repeat.

This process continues to accelerate until one of two things happens: either the deterioration becomes evident enough that the owner takes action, or the system fails and a chunk of the parapet lands on the sidewalk or street. Obviously, the latter threatens both the building and the general public. FISP helps head off such mishaps, but the steep cost curve of deferred maintenance should be another deterrent to neglect.

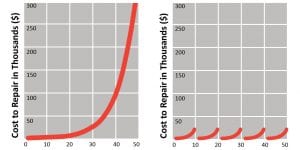

These graphs depict two distinct approaches to maintaining a typical parapet wall

The graph on the left illustrates the alarming consequences of ignoring the parapet’s condition for fifty years. The cost to restore the system to its original condition after five decades of neglect is $300,000. This includes reinforcement of the steel spandrel beam, masonry reconstruction, and replacement of coping stones.

The graph on the right illustrates the results—and profound benefits—of inspection and maintenance performed every ten years. After the first decade, the cost to restore the system to its original condition (replacement of coping caulking, repair of cracked masonry, and masonry repointing) is $30,000. After such proactive maintenance, the cost-to-repair graph is “reset,” so that ten years later, the cost is once again $30,000 ($150,000 over 50 years). This means that, between the scenarios represented on the left and right, there’s a 50% cost savings of $150,000! Few other decisions an owner can make offer savings of such magnitude.

The left graph helps answer a common query from managing agents: “Why has the building’s condition become so much worse in just the past few years?” It’s because, with deferred maintenance, the graph “takes off” over time at an accelerating rate (suddenly, to quote Hemingway) so the deterioration curve becomes precipitously steep. Systems fail with less warning, sometimes with catastrophic consequences.

Clearly, any of these failures can constitute danger and inconvenience to a building’s occupants, hazards to bystanders, and serious liability issues for the building owner or manager. When the deterioration curve is effectively flattened, both occupants and owner are better protected. The conclusion is clear: In the long run, regular maintenance avoids the threat of sudden building “bankruptcy.”

14 Wall Street, 25th Floor, New York, NY 10005

(212) 505 1133

info@superstructures.com

Subscribe to SuperScript, our email newsletter.